History

The wilderness of the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York might at first glance seem like an unlikely spot for one of the most significant training programs in classical music. But that is where the Meadowmount School of Music has since 1944 been nothing less than a breeding ground for greatness.

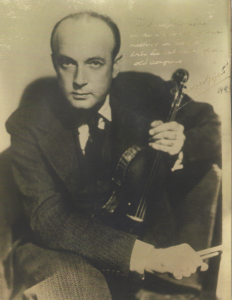

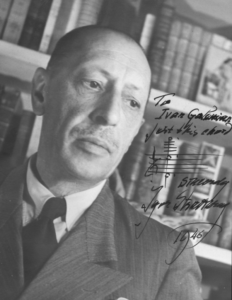

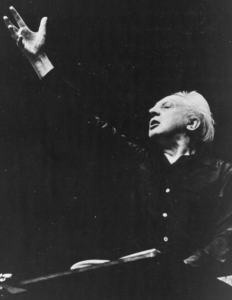

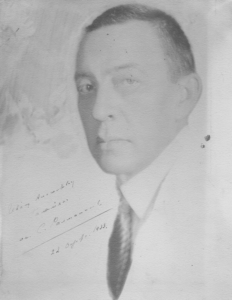

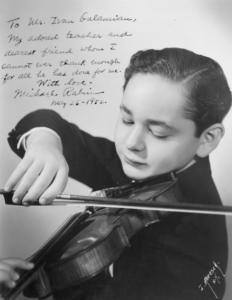

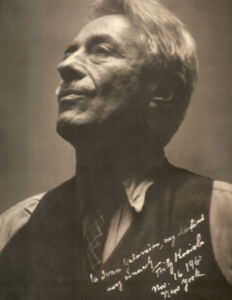

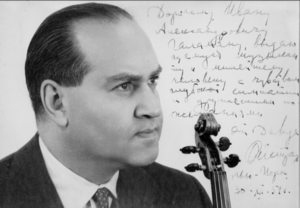

When a 34-year-old violinist named Ivan Galamian stepped off a ship in New York City in 1937, one could say that the future of American string playing had arrived. The Persian-born Armenian musician raised in Russia had already acquired a reputation, first as a prodigy, making his acclaimed recital debut in Paris at the age of 21, then as a busy concert artist, and subsequently as an astonishingly effective teacher. Having joined the faculty of the Conservatoire Russe de Paris not long after his debut, he was dubbed “Ivan the Terrible” for his exacting methods, but his success with young violinists led to a thriving teaching practice in Europe and the U.S. By 1937, however, the political situation in Europe had worsened to the degree that Galamian decided to emigrate – with the ambition of becoming the greatest violin teacher in America.

Once in New York, Ivan Galamian began teaching, both privately at his small West 54th Street apartment and at the Henry Street Settlement on the Lower East Side. His friend Gregor Piatigorsky, the celebrated Russian cellist, had settled in Elizabethtown, in the Adirondack Mountains, and when Galamian paid him a visit, he fell in love with the area and the white birch trees that reminded him of his Russian home.

On one of his trips upstate, Galamian was invited to the birthday party of Edward Lee Campe, a wealthy manufacturer of men’s clothing, where he was introduced to Judith Johnson, a sea captain’s daughter. In November 1941, they were married.

Videos

The Beginning

Galamian had confided to his bride that he wanted to start his own music school. Not just any run-of-the-mill academy, either, but an institution with a very specific purpose: total immersion in the study of string instruments. Too often, Galamian felt, his students – even the pupils he was now teaching at prestigious conservatories like Juilliard and the Curtis Institute – would neglect their studies during the summer months. Galamian envisioned a school where the summer would serve as a time for more intensely focused practice. He believed that dramatic improvements would arise from such a disciplined approach.

In the beginning of 1944, he found the perfect place: a lodge built by an inventor named John Milholland, one of the creators of the pneumatic tube, outside the community of Lewis, New York. The Galamians leased the Milholland property, and in the summer of 1944, Galamian invited approximately 30 students to come and study with him. Taking its name from the Milholland estate, the Meadowmount School of Music had begun.

The same year of Meadowmount’s creation, Galamian received a professorship at the Curtis Institute (he would become the head of the violin program at Juilliard in 1946). The increase in salary brought the dream of buying the lodge and the surrounding land closer to reality. And when Judith convinced Edward Lee Campe, the man whose birthday party resulted in her introduction to Galamian, to carry the mortgage on the property (which he did for 22 years, interest-free), the purchase was complete.

From the beginning, the regimen was demanding. After breakfast at 7:00 am, the students retreated to their practice rooms. Every pupil had to practice four hours in the morning, each hour divided into 50 minutes of playing followed by 10 minutes of rest. A break for lunch was followed by another hour of practice in the afternoon, along with private lessons.

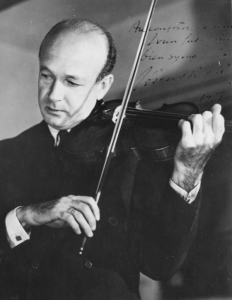

Today, the Meadowmount routine is remarkably similar to that of the camp’s earliest years. Galamian’s methods were rooted in discipline and purposeful routine. A quote from the Roman philosopher Seneca hung on his studio door: “Most powerful is he who has himself in his own power.” To him, carefully structured practice – good quality practicing, and lots of it – was the tool to transforming raw talents into professional artists.

By 1950, Meadowmount’s enrollment had increased to 54 students, and the camp had outgrown its existing facilities. Recognizing the need to expand, the Galamians purchased The Lilacs, a two-story home that the Milholland family had once owned. Around that same time, residents of the area – who had dubbed Meadowmount “Fiddler Hill” – had begun to realize that something special was happening at this Adirondack outpost. People started showing up in larger numbers to hear the students play their recital programs, and a proper concert hall became necessary.

Galamian had a unique idea for Meadowmount’s performance space. He wanted to line the inner walls with white pine, the same high-quality wood used in constructing the top of a violin. Playing instruments containing white pine in a space surrounded by white pine would, he assumed, produce beautiful acoustic results. Edward Lee Campe, who had given Meadowmount its interest-free mortgage, funded the concert hall as a gift to the school, and to this day the hall bears the name of Edward Lee and his wife, Jean.

Who Taught There

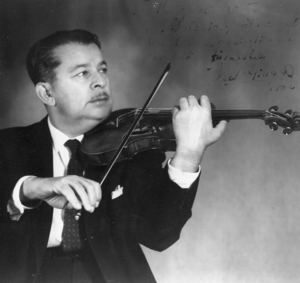

Meadowmount rapidly became a haven for a “who’s who” of guest instructors. Among the first were early 20th century string legends: Piatigorsky, and violinists Joseph Szigeti, the Hungarian mastermind who had commissioned concertos by Bela Bartók and Ernest Bloch; Zino Francescatti; Isaac Stern. During the 1950s, Meadowmount’s faculty deepened: highly respected cellist Leonard Rose arrived near the beginning of the decade, returning for many years, and two of Galamian’s prized assistants, Sally Thomas and Dorothy DeLay, started taking on greater levels of responsibility, the starting points of two extraordinary teaching careers.

And then there was Josef Gingold, the violinist whose legend as a teacher rivals that of Galamian. Initially, Gingold arrived at Meadowmount with no intention of teaching there, visiting merely to check up on his prize pupil at the time, a young teenager from Bolivia named Jaime Laredo. Galamian engaged the man in a vigorous conversation about teaching theories, concluding with an offer of a teaching position. The next summer, Gingold was at Meadowmount, coaching close to 20 string quartets during that one season.

Who Studied There

At one point in the 1960s, one student string quartet featured the following membership: Itzhak Perlman and Young-Uck Kim on violin, Pinchas Zukerman on viola, and future contemporary music champion Paul Tobias on cello. During those years, two pupils from Sally Thomas’s studio – Zukerman and Kyung-Wha Chung – faced off against one another in the Edgar Leventritt Competition finals.

And that decade, Meadowmount trained emerging soloists like Lynn Harrell, Ani and Ida Kavafian, James Buswell, and Miriam Fried, along with a small galaxy of future orchestral concertmasters.

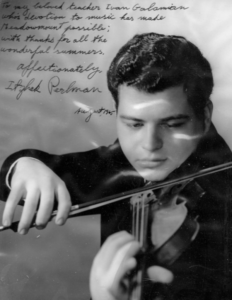

“It was a very special place for me in that regard,” Lynn Harrell recalled. “I had never been any place where there were so many extraordinarily talented people who were so dedicated to making music.” For Itzhak and Toby Perlman, their Meadowmount memories involve a marriage proposal. Itzhak and Toby now run the Perlman Music Program on Shelter Island, NY, and the operation’s guiding principles are adapted from their days in the Adirondacks. “The practice regimen is the same as Meadowmount,” Perlman said. “Four hours of practice in the morning; four hours of 50-minute sets. And in a lot of ways, the idea is the same, too. We want to get young musicians excited about what they’re playing.”

Pinchas Zukerman credits Meadowmount with everything from forcing him to play viola – an instrument on which he is now hailed as a virtuoso – to transforming his attitude about playing music. “There is an emotional side that is very wild when you are a teenager,” he explained. “Then there is the practical side, which is lagging behind. Well, Mr. Galamian understood the psychological behavior in a teenager’s life. He knew how to slow the entire process down. When you do that, your whole existence becomes clearer.”

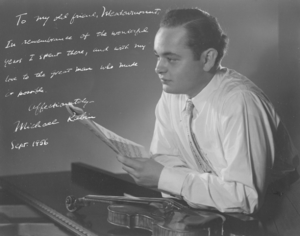

“To be with so many people my own age, to see what they (were) up to,” recalled Yo-Yo Ma – “that was very important to me. And, of course, to be with so many wonderful older musicians was quite a heady experience for a 15-year-old kid.” Before Meadowmount, Joshua Bell had never practiced his instrument for more than an hour a day. “Some of the most incredible musical moments of my life” were at the school, Bell stated. “I can’t even imagine how many things that are a part of me now are things that all began at Meadowmount.” And James Ehnes said, “Sometimes, I think of the incredibly short period of my life that I was actually there. Four summers, seven weeks each summer, and only six weeks that first summer. And yet so much changed for me as a musician and as a person during that time.”

After Ivan Galamian

On April 14, 1981, Ivan Galamian passed away. That summer, the camp opened on time, filled to capacity. Galamian’s message remained alive and well.

Judith Galamian continued overseeing the camp’s administrative work until her own passing in 2005. A series of directors were appointed by Meadowmount’s governing body, the Society for Strings. In 2021, Janet Sung, an international violin soloist and Meadowmount alumna, was appointed Artistic Director. Her leadership is poised to move the school into the future, expanding resources and opportunities, revitalizing the school campus, and engaging with the Adirondack community and beyond, while maintaining the core mission and artistic vitality at the highest standard.

While the campus and its environs have been modernized since 1944, Ivan Galamian would recognize the place if he walked in today. Seven decades after its founding, students follow the same practice schedule, receive instruction using the same fundamental teaching methods, and obey the same basic code of camp rules. Top-level musicians continue to flood the office with applications every year. First-rate graduates continue to populate the highest echelon of soloists, chamber musicians, concertmasters, section leaders, and teachers around the world.

In 1937, when Galamian pronounced that he planned to become America’s greatest violin teacher, the words likely sounded nothing but boastful. Today, however, musician after musician confirms that, particularly in one bucolic spot in the Adirondacks, the tireless instructor proved to be everything that he promised.

Adapted from “Strings of History” by Benjamin Pomerance

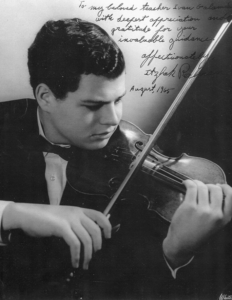

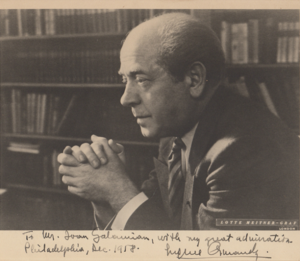

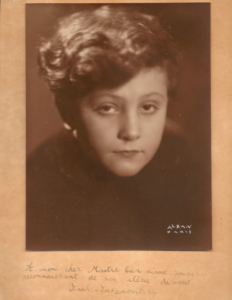

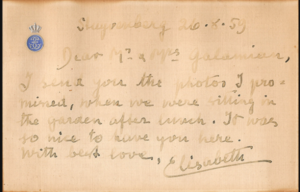

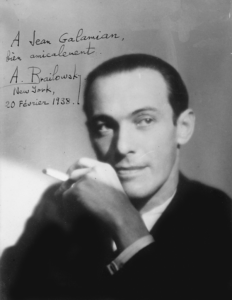

The Galamian Photo Collection

Meadowmount and the Milholland Family

Inez Milholland Boissevain at the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C.

Inez Milholland Boissevain at the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C.

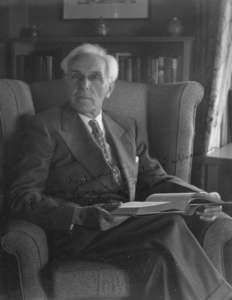

Before it became a music school, Meadowmount, a 1,000-acre tract in the Adirondack Mountains, was the estate of the Milhollands, a family that holds a prominent place in the industrial growth and civil rights struggles of the United States in the early 20th century.

The family’s American story began when John Milholland emigrated to the United States from Ireland in the 1850s and settled in Lewis, New York. He married Mary Moore, and they had a son and a daughter. In 1863, the family’s house burned to the ground, and Mary and their daughter died in the fire. John took his son, John Elmer Milholland, back to Ireland, but after two years they returned, and John opened a confectioner’s shop.

While in high school, John Elmer attracted the interest of a local Congressman in New York City, William Walter Phelps, who arranged for his tuition to be paid at New York University. After two years there, John Elmer dropped out and became a journalist, first at the Ticonderoga Sentinel, and eventually at the New York Tribune, where he became the chief editorial writer.

John Elmer also invested in the Batcheller Pneumatic Tube Company, eventually becoming its president. The company was instrumental in the creation of pneumatic tube lines, systems that propel cylindrical containers through networks of tubes by compressed air, that became for a time widely used in mail delivery.

Through these and other ventures, he became a wealthy man. He purchased a parcel of land in Lewis that would become the family estate. He also used considerable amounts of money to fund civil rights activists, initially Booker T. Washington, and then W. E. B. Du Bois, and Mary Ovington and her work with disenfranchised African Americans in New York. Milholland helped in the founding of the Phipps Houses, which is currently the largest not-for-profit developer, owner, and manager of affordable housing in New York City, and founded the Constitution League, the predecessor of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Milholland was the NAACP’s first treasurer. In 1928, a bust of Milholland was erected at Howard University.

John Elmer Milholland had married Jean Torrey, and they had three children, Vida, John, and Inez. Both Vida and Inez became notable activists for women’s rights. Inez was a lawyer whose interests included prison reform and equal rights for African Americans; she joined her father as a member of the NAACP. She gained national fame when, astride a white horse, she led the historic March 3, 1913, Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, DC. She was also a leading figure on Henry Ford’s unsuccessful Peace Ship expedition of late 1915, crossing the Atlantic with a team of pacifist campaigners who hoped to spur a negotiated settlement to the First World War.

Inez became a martyr to suffrage when she collapsed and died at age 30 near the end of a grueling cross-country campaign for the National Woman’s Party in support of a federal suffrage amendment. Her final public words, “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” became a rallying cry of the NWP. Inez was honored with the first memorial service for a woman ever held in the U.S. Capitol.

After her death, Inez’s father and the people of Lewis and Elizabethtown renamed Mount Discovery, a mountain on the Milhollands’ Lewis property, Mount Inez, in honor of “their most illustrious citizen.” More than a hundred years later, the name change became official – just in time for the 100th anniversary, in the summer of 2020, of the 19th amendment that granted the Women’s Right to Vote.